Descrizioni dell'Orto botanico di Padova nel tempo

Presso la biblioteca dell'orto botanico (ora Biblioteca storica di medicina e botanica Vincenzo Pinali e Giovanni Marsili) si conservano i testi che fin dai primi anni della sua vita han descritto l'orto botanico universitario più antico.

L'horto de i semplici… edito dal Porro nel 1590 presenta la prima immagine del giardino ed è anche una sorta di quaderno per lo studio dove le aiuole dei quarti dell'hortus conclusus illustrate presentano un numero al quale corrisponde una casella vuota e pronta alle osservazioni manoscritte dello studente.

Dal '500 a tutto il '700 le guide dell'ateneo e della città si soffermano sull'orto specificando la sua importanza e descrivendo il giardino e gli edifici che lo compongono.

A metà dell'Ottocento vi sono alcuni testi dedicati alla storia dell'orto botanico con il prefetto Roberto De Visiani come autore. Questi compare anche come curatore dell'edizione di un testo inedito del suo predecessore Giovanni Marsili, le Notizie del pubblico giardino de' semplici di Padova compilate intorno l'anno 1771. Il Ceni presenta invece una guida dell'orto completamente illustrata nel 1854.

Continuano le guide di Padova che presentano anche l'orto, edite nel 1842, nel 1855 ed una in lingua francese nel 1856.

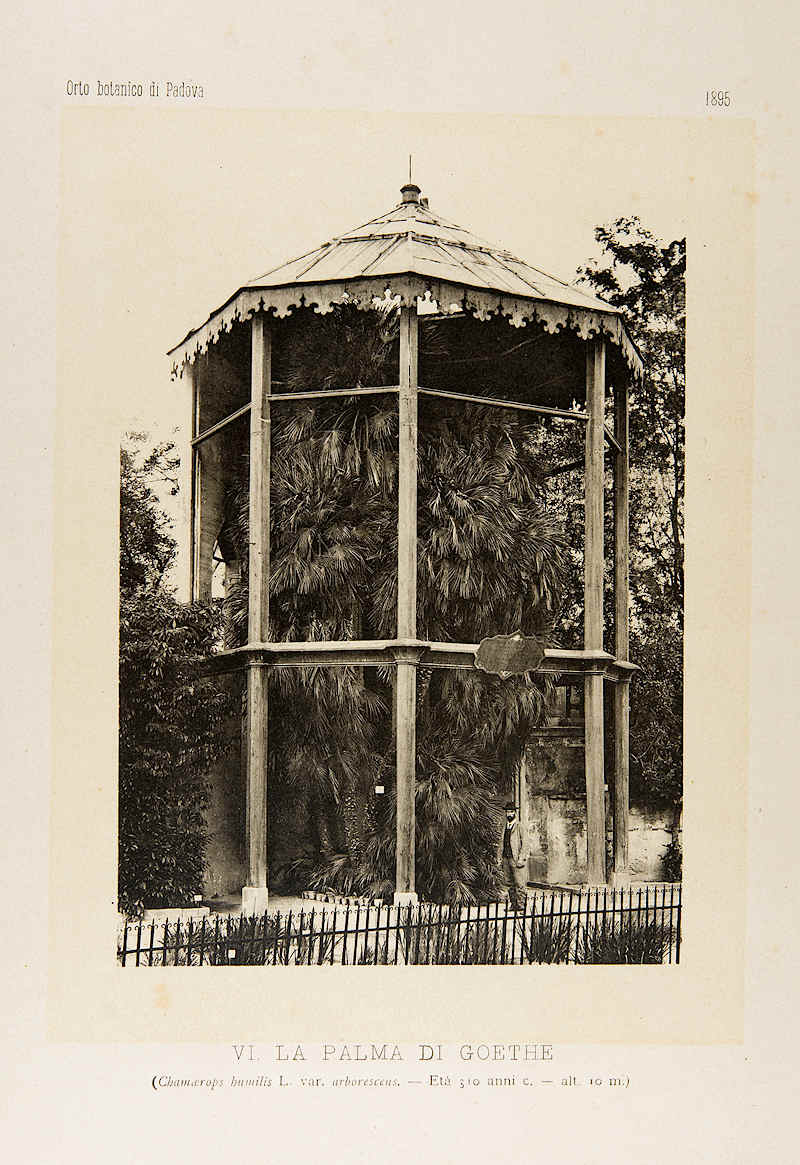

Dopo un contributo del De Toni sugli alberi storici, il prefetto dell'orto Pier Andrea Saccardo con L'orto botanico nel 1895 fa il punto della situazione alla fine del secolo.

Qui presentiamo la riproduzione di un esemplare che contiene anche fotografie coeve dei luoghi descritti.

Augusto Beguinot con le sue relazioni illustra l'Istituto e la sua attività nei drammatici anni della guerra mondiale 1915-1918 e ci dona una descrizione dell'Archivio ancor oggi necessaria per la ricerca storica nel posseduto manoscritto della biblioteca.

Alcune vedute e planimetrie conservate in biblioteca ci permettono di vedere l'orto così com'era nella seconda metà dell'800. Carlo Matscheg nel 1862 ne dà un'immagine romantica, ritraendolo in tre acquarelli delicati dove tra gli alberi storici e la vasca polilobata passeggiano o sostano delle signore in crinolina, un gentiluomo e due bimbe con cuffietta e bambola. Il pittore e decoratore bellunese, 1831-1901, lavorò nel Veneto e diede prova di sé anche in un album litografico dedicato al lanificio Rossi di Schio con vedute del giardino dello stabilimento.

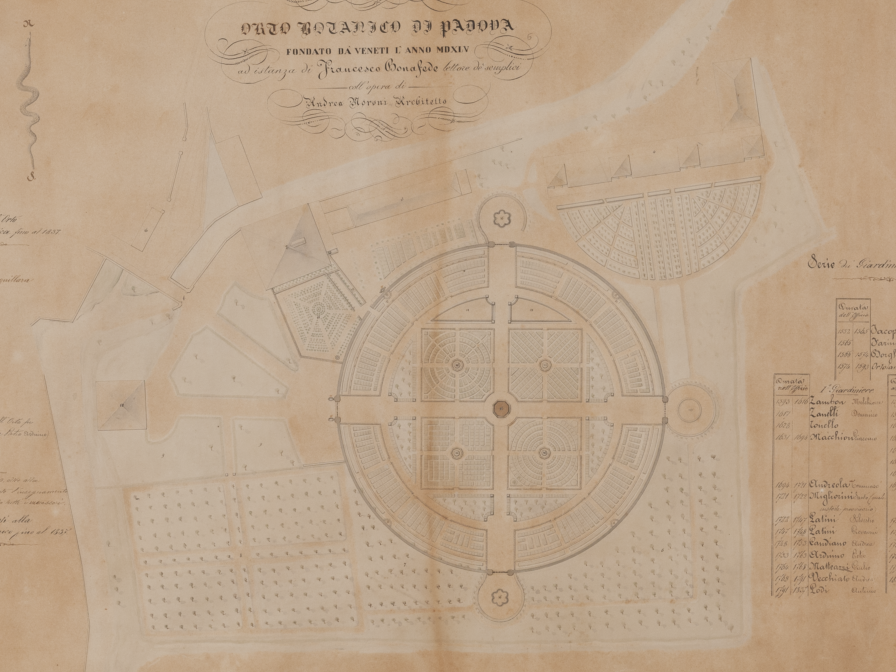

Le planimetrie invece son disegni tecnici che riportano gli edifici e le partizioni della terra dell'orto illustrandone gli alberi presenti e riportando le liste dei Prefetti e giardinieri succedutisi nel tempo.

Un prospetto del 1871 mostra le nuove serre che occupano il lato nordest fra le vecchie serre e la casa del Prefetto.

L'orto nella sua struttura e disegno storico non appare cambiato nel tempo ma conserva la struttura voluta nel XVI sec. dai fondatori.

è un servizio del

è un servizio del