Erbari illustrati della biblioteca dell'Orto botanico di Padova

Beguinot nel 1913 nell'illustrare il cosiddetto Archivio dell'Orto botanico parla di una collezione composta da manoscritti, testi a stampa ed erbari di piante secche. Desideriamo qui presentare una scelta di volumi con rappresentazioni manoscritte di piante, degli erbari illustrati che ci parlano dell'evoluzione della botanica e dell'illustrazione botanica.

Le opere son state prodotte dal XV al XIX secolo e son arrivate in biblioteca in vari momenti.

Al fondo più antico appartengono tre opere legate all'attività didattica e alla passione per il collezionismo librario del prefetto dell'Orto Giovanni Marsili (1727–1795).

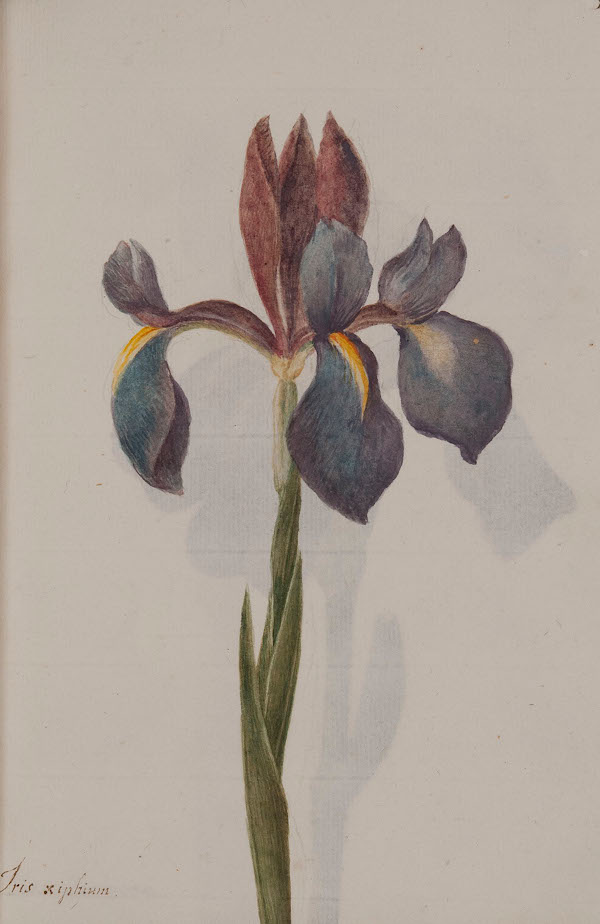

Si tratta per prima dello Pseudo Apuleio, erbario manoscritto e illustrato nella seconda metà del '400 in area veneta che riporta immagini di piante officinali di fresco naturalismo o di più astratta raffigurazione e addirittura la versione fantastica della mandragola resa in maniera credibilmente realistica (Ar.26).

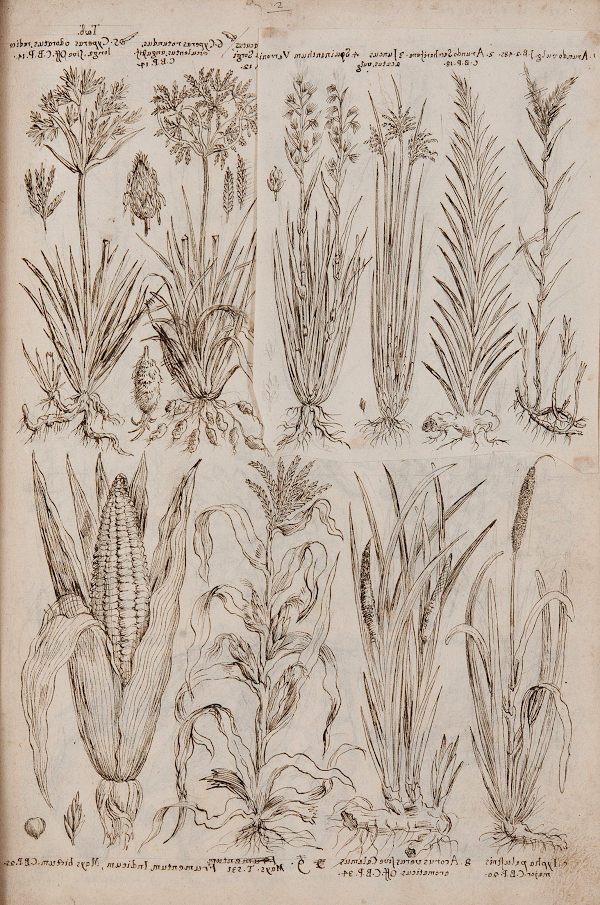

Inoltre si conserva l'erbario dedicato alla flora del monte Baldo di Bartolomeo Martini (Ar.27 vol. 1, vol. 2), un erborista di Soave (1626–1720). Le illustrazioni di tale opera con la loro impostazione grafica con la legenda con i nomi delle piante secondo la nomenclatura di Bauhin son duplicate in un altro volume di simile fattura e tali modi espressivi troviamo in altri testi dedicati alla flora del veneto arrivati più tardi in Orto botanico (1904).

Legato all'attività didattica e alle piante coltivate in orto è l'erbario illustrato con le impressioni a fumo delle piante preparato da Giovanni Crasso, studente dell'Orto, e legato in volume secondo la classificazione botanica di Tournefort dal prefetto Marsili nel 1784. L'impressione a fumo fu una tecnica con cui si stampava utilizzando direttamente la pianta cosparsa di fuliggine e ottenendo così immagini di sorprendente delicatezza e realismo.

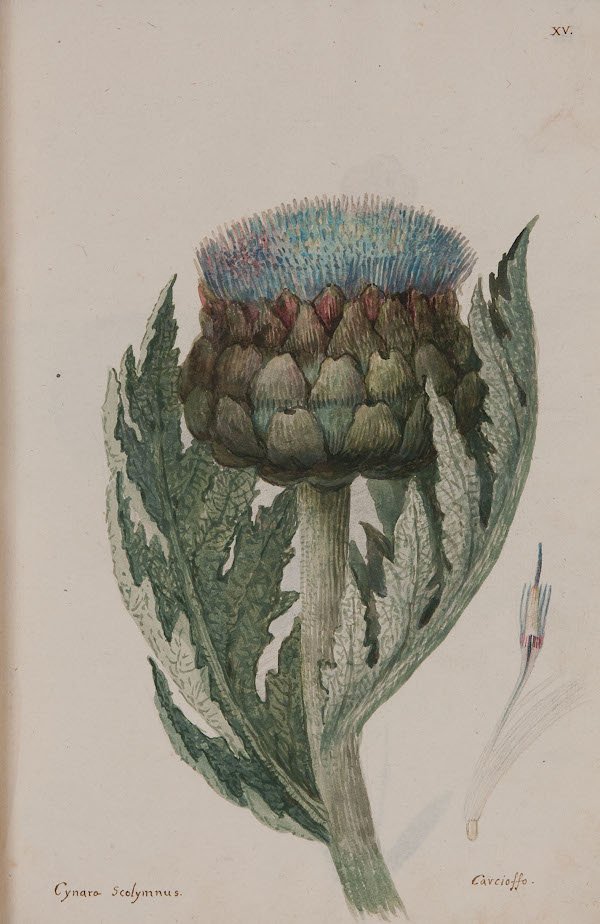

Alla morte di Marsili la raccolta libraria fu acquistata dal prefetto successivo Giuseppe Antonio Bonato (1753–1836) che alla fine la legò all'Università con il suo patrimonio librario costituendo così la biblioteca dell'Orto botanico come istituzione dell'ateneo (1835). A questi risale la raccolta Piante del R. Orto Botanico di Padova composta da 360 tavole dipinte a colori fra tavole didattiche intorno agli argomenti delle lezioni di botanica e immagini dei fiori coltivati nell'Orto. Dalle eriche alla ninfea, dalle rose alla magnolia e ad altre piante ancora il volume ci offre un superbo bouquet dal gusto romantico.

Con la direzione di Pier Andrea Saccardo la biblioteca tornò ad accrescersi di erbari illustrati o di piante seccate prodotti da speziali e naturalisti veneti grazie alle relazioni e all'interesse per la storia della botanica di tale prefetto.

Nel 1901 Saccardo comprò per 150 lire da Angelo Zennaro di Chioggia i 12 fascicoli di circa 100 tavole ognuno de Cento fiori colti nel loro mese… (vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3) dell'abate Angelo Franciosi (1759–1822). Nativo di Adria tale religioso era poi vissuto presso la famiglia materna dei Vianelli a Chioggia e lì fu botanico dilettante e pittore di queste tavole dedicate alle piante della zona, accompagnate dai loro nomi e note sulla loro raccolta e caratteristiche. Dai Vianelli l'opera passò allo Zennaro. In una lettera di questi datata Chioggia 15 maggio 1901 e conservata in biblioteca egli si raccomanda che il Saccardo citi la provenienza dei volumi a ricordo della famiglia e intesta la carta: Angelo Zennaro Orefice Giojelliere Calle Manfredi 218 Chioggia. Come in altre occasioni l'acquisto stimolò lo studio dell'opera e della sua provenienza da parte di Saccardo che poi diede alle stampe il suo contributo alla storia della botanica, La iconografia botanica dell'ab. Angelo Franciosi… Padova 1902.

Nel 1902 il farmacista veneziano Girolamo Dian donò al Saccardo una raccolta cospicua di erbari illustrati, di piante secche e di testi manoscritti di due speziali e botanici veneti del XVIII secolo. Si tratta del materiale di Gian Girolamo Zannichelli (1662–1729), speziale all'Ercole d'oro presso santa Fosca a Venezia, e del detto Bartolomeo Martini a lui amico. Il materiale di Zannichelli e di Martini era passato alla farmacia Galvani in campo Santo Stefano a Venezia in deposito da parte degli eredi Zannichelli che nella persona di Carlo lo lasciavano poi al Dian, genero del Galvani. Egli quindi lo donava all'Orto botanico di Padova dove presso l'università già si conservava la raccolta naturalistica dello Zannichelli (1759). Saccardo in più contributi poi condensò il suo lavoro su tali raccolte botaniche e sui loro autori (1898, 1904, 1907).

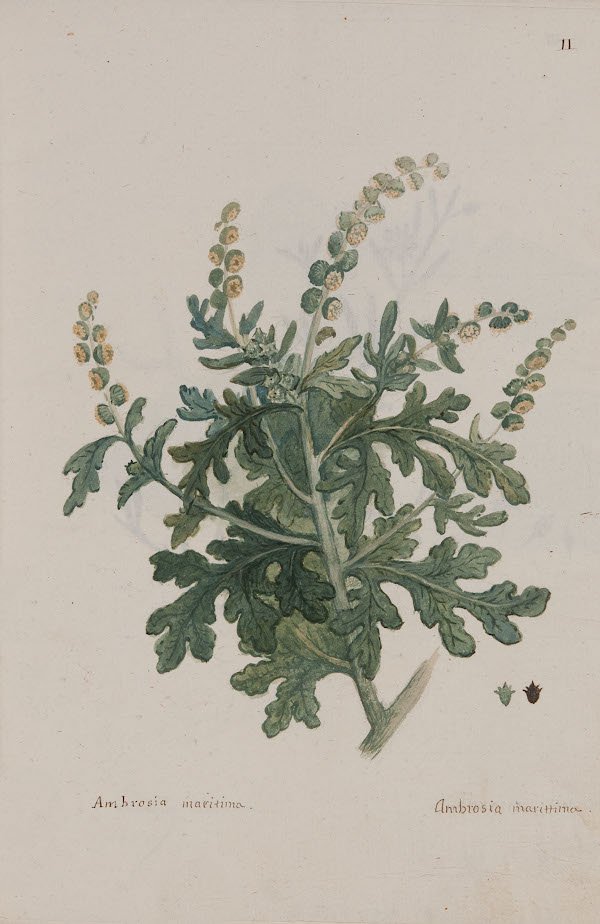

Tra queste reliquiæ zannichelliane vediamo per primo un codice che contiene 116 tavole su carta e una su pergamena dipinte da una mano sconosciuta. Si tratta di una parte delle immagini di piante pubblicate nel 1735 col titolo Istoria delle piante che nascono ne' lidi intorno a Venezia, sul verso portano note sul giorno e il luogo della loro raccolta avvenuta dal 1722 al 1726 e sul recto il nome linneano scritto dal Saccardo. Fra le più significative l'eringio a c. 21 e a c. 49 la Ruta patavina, Haplophyllum patavinum secondo la nota di Saccardo, nella sua più antica raffigurazione.

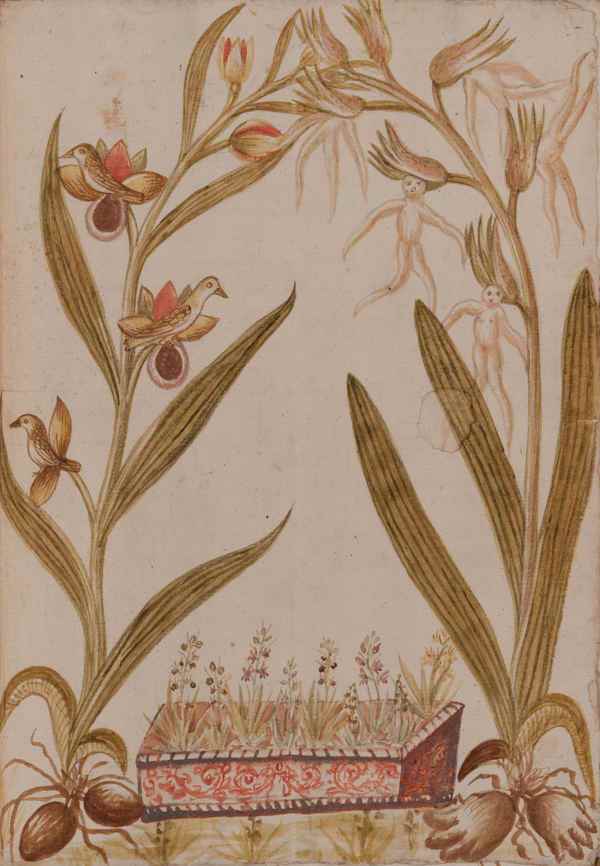

Delle Orchidi è un codice dedicato alle orchidee italiane, 65 immagini colorate a cui son premesse due piante fantastiche, una con fiori in forma d'uccello l'altra in forma umana (Ar.7). Assieme si conservano gli elenchi manoscritti dei nomi delle orchidee secondo la nomenclatura Bauhin e Tournefort e secondo Linneo. Secondo Saccardo (1904) il codice è copia di parte di un altro di Antonio Micheli, studioso fiorentino corrispondente dello Zannichelli.

Flora exoticha… e Flora alpestre… son due volumi di Bartolomeo Martini, simili al manoscritto illustrato appartenuto a Marsili (Ar.27 vol. 1, vol. 2). E tutti i testi di Martini son simili al Mons Baldus naturaliter figuratus… (F.Ve.27), che un lungo passaggio di mani ha portato alla biblioteca. Il F.Ve.27 riporta una nutrita serie di segni di appartenenza da cui vediamo che fu della collezione Fracchia, famiglia di farmacisti di Treviso, poi della collezione privata di Pier Andrea Saccardo, poi di suo genero Alessandro Trotter che lo donò ad Achille Forti in ricordo del suocero loro comune maestro. Nel 1937 fa parte del lascito testamentario a favore dell'Orto botanico del munifico botanico Forti. Nati nello stesso ambito e sugli stessi argomenti, questi volumi testimoniano una ininterrotta tradizione della produzione di testi illustrati manoscritti.

Tornando al dono di Dian non possiamo dimenticare due volumi in quarto di immagini della flora rilevata durante il viaggio di Zannichelli al monte Cavallo in Friuli (Ar.9 vol. 1, vol. 2). Si tratta di due volumi, il primo di 100 tavole e il secondo di 82 arrivate sciolte nel 1905 da Dian e rilegate poi dal Saccardo. Oltre alle piante si trova il ritratto della Salamandra atra. Negli Opuscula botanica posthuma… stampato a Venezia nel 1730 viene edito il resoconto di questa esplorazione botanica fatta nel 1726 con Pietro Stefanelli, giardiniere della famiglia Nani di Venezia.

Un ultimo gruppo di 182 c. di tavole botaniche sciolte di Martini fu regalato da Cesare Garbelli nel 1904 secondo una nota manoscritta da Saccardo e legate assieme in un volume diviso in due parti (Ar.29). Alcune tavole hanno una fattura molto fine, per esempio i tulipani, ma poche portano la didascalia solita con la nomenclatura e molte invece i danni derivati da cattiva conservazione come macchie, lacerazioni, segni di vecchi restauri.

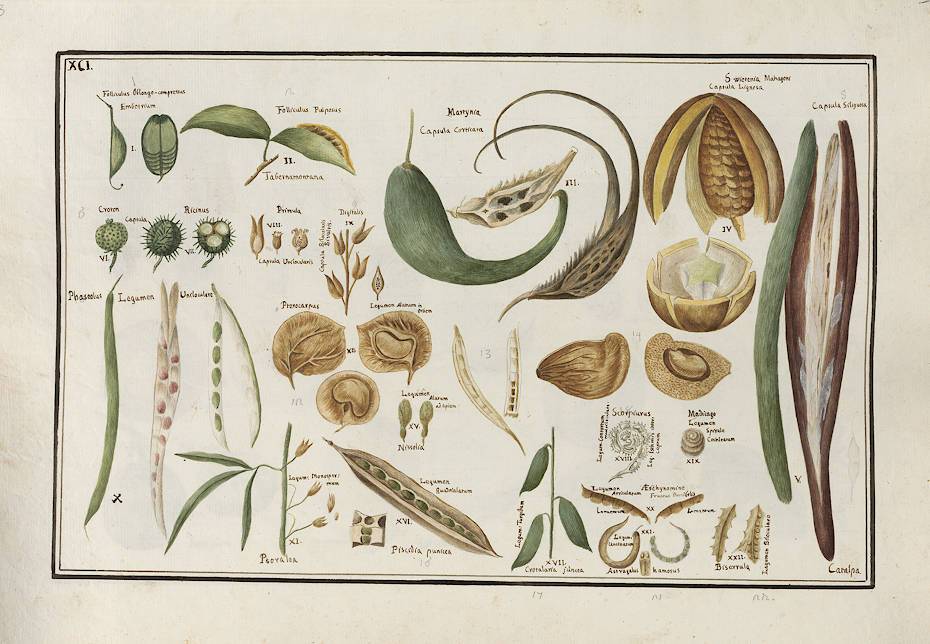

Nel novembre 1913 due volumi di illustrazioni botaniche, per lo più disegni a penna tratti da opere di vari botanici e qualche immagine dipinta, vennero offerti per 30 lire dal veneziano Egidio Gamberini al prefetto Saccardo. Il Gamberini afferma di averli comperati assieme ad altre cose antiche da un orefice di Piacenza, in buoni rapporti con famiglie nobili e comunità religiose. Il Saccardo considerò come autore di questi pezzi Giovanni Battista Morandi, che fu pittore ufficiale all'Orto botanico di Torino dal 1732 al 1741 e a cui si ascrive un corpus di immagini manoscritte conservate oggi fra Milano, Pavia e Torino e l'edizione a stampa di Historia botanica practica (Milano, 1744 e 1761. Una versione digitale si trova alla Sapienza Digital Library).

Nel codice Ar.52 vi sono pagine che presentano alcune fini immagini di piante e fiori con didascalie con la scrittura in senso contrario come si conviene per l'incisione, che poi porterà ad una stampa con la scrittura corretta, ma solo 19 son state riconosciute nell'Historia… poi stampata. Vi son anche immagini ritagliate, incollate, sciolte come se le carte fossero state usate non solo per la consultazione. L'unica immagine dipinta a colori vivaci precede le altre. Vi sono anche note manoscritte dedicate ad alcune piante per esempio la vaniglia, il convolvolo e il caffè per cui si riporta anche il disegno di un ramoscello fiorito con didascalia: “di grandezza naturale, delineato e dipinto dal vero dal Cav. Giovambattista Morandi in Pisa l'anno 1722”.

Una ricevuta conservata con due lettere del Gamberini nel volume Ar.53 ci testimonia che l'acquisto poi si concluse per 20 lire. Il frontespizio manoscritto di questo codice cita un padre Zaccaria di Piacenza collegando così il volume all'ultimo luogo accertato di provenienza:

“Questa per quanto piccola fatica sia consacrata da me, padre Francesco Zaccaria da Piacenza dalla provincia bolognese dei Minori Riformati amante della virtù della botanica, al sapientissimo Creatore delle piante, la gloria dell'eterno nome del quale tante foglie quante lingue proclamano”.

Il frontespizio è seguito da un disegno colorato con palme, uccelli e un castello fantastico di gusto esotico che sembra richiamare il gusto orientaleggiante di certa decorazione settecentesca. Qualche tocco di colore si trova nelle ultime carte specie nella “Palma indiana”. Le condizioni dei due volumi, coperte di carta decorata consunta e con carte distaccate, evidenziano un uso intenso.

È interessante vedere che qui come in altri volumi Saccardo pose note manoscritte di carattere bibliografico sui volumi stessi o relative alla loro acquisizione, anche conservando lettere e ricevute relative all'acquisto proprio nel volume. Inoltre molto spesso il Saccardo, botanico sistematico provetto, aggiunse il nome linneano alle piante ritratte che portavano quello che si riferiva ad altri sistemi classificatori come quello di Bauhin o di Tournefort.

Una nota manoscritta da comunicazione del botanico Achille Forti su di una raccolta anonima di tavole botaniche a colori ci introduce alla storia della provenienza del codice Ar.57. Con la data “Padova 30 marzo 1927” si annotò infatti che tale volume tramite il Forti arrivava in dono all'Orto da Ottorino Biasi pretore di Verona. Con l'aiuto di un necrologio del Forti per il botanico Caro Benigno Massalongo datato 1928 veniamo a sapere che il sacerdote e professore di Scienze Naturali al Seminario di Verona Giovanni Battista Pedretti fu coordinatore dell'illustrazione di almeno due opere botaniche, questa dell'Orto e una, Raccolta di diverse piante designate dal naturale… appartenuta al Massalongo ora alla Biblioteca civica di Verona e attribuita a un certo Pietro Saccomani. Chi fu Saccomani e se lavorò anche a queste tavole non sappiamo. Forse l'esame del volume a Verona ci potrebbe aiutare.

Le collezioni della biblioteca sono ora confluite nella nuova Biblioteca storica di medicina e botanica Vincenzo Pinali e Giovanni Marsili.

Per approfondimenti visita la mostra virtuale L'illustrazione botanica

Bibliografia

Voce “Morandi” in La botanica in Italia, di P.A. Saccardo. Venezia: C. Ferrari, 1895 p. 113 e 1901 p. 75.

Giovanni Girolamo Zannichelli, cenni di P. A. Saccardo. Genova: Cominago, 1898.

Carteggio relativo all'acquisto dei volumi di Franciosi Ar.46,1-3, (1900–1901), in Ar.Racc.2(b) nella Biblioteca dell'Orto botanico di Padova (ora Biblioteca storica di medicina e botanica Vincenzo Pinali e Giovanni Marsili).

La iconografia botanica dell'ab. Angelo Franciosi, veneto. Notizie storiche e revisione botanica, di P.A. Saccardo. Padova: Randi, 1902.

Appunti intorno alla Iconographia Taurinensis 1752–1868, di I. Chiapusso-Voli in Malpighia, A. 18 v. 18 (1904) p. 305-310.

I codici botanici figurati e gli erbari di Gian Girolamo Zannichelli, Bartolomeo Martini e Giuseppe Agosti esistenti nell'Istituto botanico di Padova… di P. A. Saccardo. Venezia: C. Ferrari, 1904.

Un manipolo della flora del monte Cavallo desunto dalle iconografie inedite di G.G. Zannichelli Nota del prof. P. A. Saccardo… in Atti del Reale Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, AA. 1906–1907, t. 66 pt. 2 p. 625-642.

Le piante figurate negli acquarelli di un codice finora ignoto, di C. Massalongo. Venezia: C. Ferrari, 1914.

Bibliographical notes. 72. Morandi's “Historia Botanica Practica”, di J. Britten in The journal of botany British and foreign, v. 56 (1918) p. 212-217.

I materiali di archivio del R. Istituto ed Orto Botanico di Padova, di A. Beguinot. Messina: Stab. Tip. dell'Avvenire, 1923.

Caro Benigno Massalongo nato a Verona, 25 marzo 1852, morto a Verona, 18 marzo 1928, di A. Forti. Firenze: Soc. botanica italiana, 1928. p. 259-291. Estr. da: Nuovo giornale botanico italiano, n.s., vol. 35.

Iconografia botanica ed erbari, di G. Forneris, F. Montacchini, C. Martoglio in Erbari e iconografia botanica storia delle collezioni dell'Orto Botanico dell'Università di Torino, a cura di F. Montacchini… Torino: Allemandi, 1986 p. 73-137.

Erbari, di F. Menegalle in La curiosità e l'ingegno… Padova, 2000.

I manoscritti medievali di Padova e provincia…, a cura di Leonardo Granata… [et al.]. [Venezia]: Regione del Veneto…, 2002 n. 151.

Il Fondo Marsili nella Biblioteca dell'Orto botanico di Padova, a cura di A. Minelli, A. Angarano, P. Mario. Treviso: Antilia, 2010.

Giovanni Girolamo Zannichelli speziale a Venezia e il suo tempo, di C. Lazzari. Venezia, 2016.

è un servizio del

è un servizio del